On Sunday I posted about contemplating symbols of mortality as a part of one's Masonic practice. (I'll include a link to that post below.)

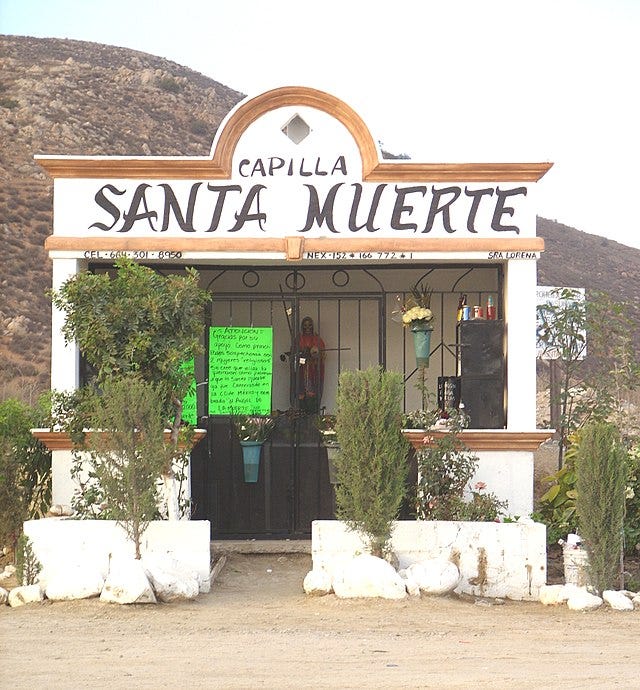

As a part of that post, I went off on a bit of a tangent about the rapidly growing devotion in Mexico (and to a lesser extent the US) to the folk saint Santa Muerte.

This devotion to Santa Muerte is something that I've studied for quite a few years now. It is a movement that I find truly fascinating, particularly as it, in my view, illustrates a much different perspective about mortality than the perspective that I grew up with. Long story short, I’ve read enough about it, and seen enough of it, to believe that I have a very solid understanding of it.

I imagine that the entire movement is extremely foreign to those of the English speaking world. Frankly, the imagery is scary, and could appear to be idolatry.

Perhaps it is easiest explained by saying that while it is condemned by the Roman Catholic Church, it is very much related to the doctrine of 'Intercession of the Saints1' as accepted by the Orthodox, Assyrian, and Roman Catholic churches.

But what makes it popular (it is said to be the fastest growing new religious movement in the Americas2) is the fact that it has developed without rules. It didn’t come to public knowledge until 2001 when the first public shrine was opened. There is no clergy, there is no dogma, there are very few books. It is publicly open and accepting of all. It is believed that Santa Muerte does not judge. This has tended to attract those who are otherwise badly marginalized in society.

But of course, throughout history, dogma, in its most odious sense, has always rushed in to fill any void.

Would be and actual religious tyrants always seem drawn towards running into any void in order to tell others how they must believe, how they must worship, and how they must view God.

Of course by the very nature of Deity our human understanding can never hope to comprehend the full nature of God. All we can do is fumble blindly with our limited senses, limited understanding, and limited knowledge.

God is absolute, man is limited. Hence no man can truly know the fullness of Deity.

As such, as Freemasonry teaches us, no man has any right to tell any other man what he must believe about God, or how he must worship god.

But, the tyrants try.

I limit my learning about Santa Muerte to actual books by actual respected writers. And what I'm able to pick up in person while visiting in Mexico. So I've never looked at what is out there on Social Media platforms.

But since I wrote a bit about Santa Muerte, and posted links into that essay on Social Media, I decided to see what was out there on Facebook.

I typed Santa Muerte into the search box.

The first thing I found was a group, with the following in its description:

"The group administrator(s) emphasize the importance of La Santa Muerte's 'Rules' that are to be followed by every bother and sister in the cult according to her Rosary book and the Santa Muerte Bible. It is also important that just as we are to follow her rules, that we also understand the 12 promises La Santa Muerte has made to us, her loyal Devotees."

Needless to say, I didn't bother to join the group to read any of the posts. The public devotion to Santa Muerte is new. Far too new for any 'Rules' to be developed, and certainly no 'Promises' have been given.

But that doesn't stop those convinced of their own infallibility from trying.

I had no plan or intention to write this essay, but today I ran across a quote from Brother Pike:

“The alteration from symbol to dogma is fatal to beauty of expression, and leads to intolerance and assumed infallibility.”

Our Ancient Landmarks hold that in order to be a Freemason one must believe in God.

Beyond that, we should not inquire. And indeed we should never push our own religious beliefs, no matter what they might be, on another Mason. Not in the Lodge Room, and not in the Dining Room.

“Adherence to the Ancient Landmarks – specifically, a Belief in God, the Volume of the Sacred Law as an indispensable part of the Furniture of the Lodge, and the prohibition of the discussion of politics and religion.”

-Standards of Recognition, The Conference of Grand Masters of North America, Commission on Information for Recognition. Adopted in 1952

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intercession_of_saints

https://skeletonsaint.com/

I came across Santa Muerte a few years ago, and like you was intrigued by it in the context of my larger interest in folklore and folk spirituality. I agree that the lack of dogma is a real attraction, but I think it goes deeper.

Before I start, I hold folklore and spirituality with as much respect as I do established religions. There are times when religion becomes oppressively dogmatic and folklore becomes superstitious, and neither are good, but in neither case does the abuse and misuse justify condemnation of either, as a whole.

Organized religions, since probably the dark ages, have sought to monopolize the spiritual experience and life of the people under its control. In most cases a professional clergy evolves, and once that happens there is a tendency for people to become spiritually passive and subordinate to clergy. In areas where folk religions dominate people are very active in their spiritualities. Personal spiritual experiences are considered normal, and a nearly constant active relationship between the spirit world and the physical world dominates the culture, which includes a relationship with the dead. That interactive, personal, active spirituality is the norm for most of human history and I think our evolution as a species evolved to integrate its presence.

In many places in the world today, even with highly dogmatized and regulated religion we find, especially in ethnically homogenous populations, a folk practice continued alongside the established religion, even in the face of violent persecution. The fairy faith in Celtic lands, the belief in Elves and Gnomes in Nordic lands, and the spectrum of African, Mexican and Caribbean beliefs we see in those regions. Even in Appalachia we find remnants of European and Native American folk belief still active alongside traditional religions.

These folk beliefs provide comfort, integration and an ethical system that serves those communities in a way I think most people would envy. The power of these beliefs should not be underestimated. In Iceland a few years ago a highway was routed to avoid an area believed to be inhabited by elves. In Romania a village was abandoned in the 21st century to avoid werewolves and in a nearby location anti-vampiric rites continue to this day. In the UK, the ‘Black Dog’ tradition is still an active belief system, and the last ‘Pellars’ and ‘ ‘Cunningman/woman’ were still advertising their services into the mid 20th century (and probably still do). Even in mainstream religion we see echoes of folk traditions celebrated openly, though often without awareness. There are elements of Easter and Christmas that clearly show these influences and in the west Halloween is clearly a connection to folk beliefs. In Tibetan Buddhism we see the influence of the Bon folk practices. Hinduism is barely removed from their folk traditions. In Iceland, when Christianity was enforced by the crown, it was decided the ‘old ways’ could be practiced at home and Christianity would be practiced in public. This compromise prevented many deaths and preserved fold traditions that live on until today.

Taking my cue from these modes of living I established an altar to my familial ancestors, and regularly on their birthdays and death days and on All Hallows, light and candle and incense on that altar and sit with their memories, reliving our experiences and affections. It’s a comfort to me, in a way that nothing else is, and frankly it’s helping me integrate my own inevitable death. I have other folk practices that I engage in regularly, and those practices ground me in the place I live, and connect me with my ancestors and culture.

As a society in North America, we've shunted death into a subject we don't like to talk about. We used to have rooms in our house set aside for wakes, where the bodies of the deceased were put on display until interred. Ever wonder why we call one of the places in our house a "Living Room"?

But the civil war, where men were killed hundreds of miles away, and a lack of refrigeration, resulted in the undertaking business and embalming to ship loved ones back home to be buried. This lead to the establishment of funeral homes, removing death out of the house and into a business, a one stop shop for death. From there, the subject of death was removed from the family, and it became something we just don't talk about. Why are funeral homes such hushed and solemn places? Not what you'd expect at a wake I'd imagine.

I've written up a short lecture about the entire thing, and why things like the memento mori are now shunned. It's all related.